Operation Barbarossa was the planned invasion and occupation of the USSR by the German army. It was the most lethal military conflict in the history of warfare; the exact number of casualties during the operation is greatly disputed, but estimated somewhere around 5,000,000. Hitler had anticipated a very short campaign, lasting roughly between six and eight weeks, with the capture of both Leningrad (now known as St Petersburg) and Moscow being inevitable results. This was not the case, largely because of the incredibly harsh weather conditions of the Russian winter that the German army was simply not equipped for. The Soviet army had been wholly underestimated by the Third Reich, and so the rapid victory that Hitler had expected never came. Indeed, the failure to capture Moscow can be seen as the defeat that began Hitler’s declining power on the European stage.

One of Hitler’s key aims of World War Two was to gain lebensraum – ‘living space’ – for Nazi Germany, and he sought this all over Europe, including in the USSR. He also believed the USSR was being ruled over by Jews – his notorious contempt for the Jewish race led him to want to remove such rule from the Soviet people, and repopulate the country with Germans. As a right-wing leader, he also held himself in opposition to the Communist principles of the Soviet government, and sought to remove them because of this, too. Stalin had been gaining a reputation for intense brutality, which Hitler used as his outward justification for the campaign against him.

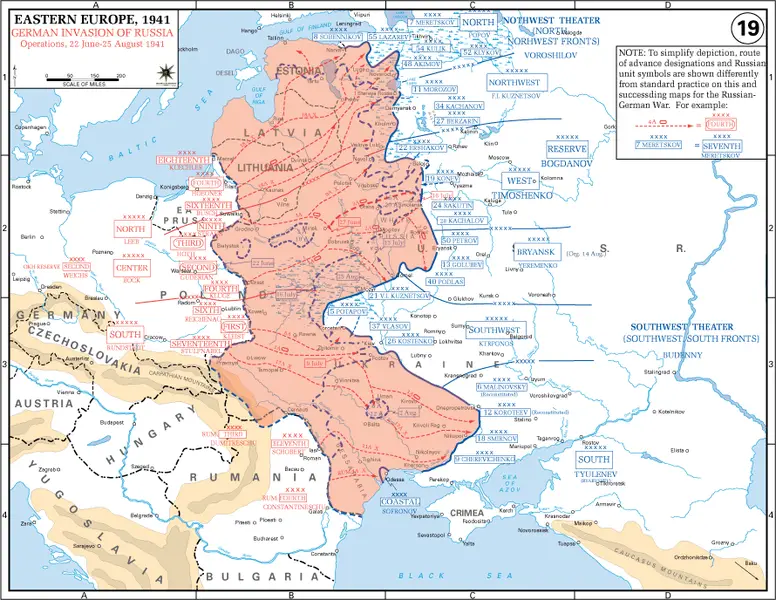

The plan of the operation was to swiftly invade and occupy the USSR, slowly taking the German army further and further East into Eurasia. The operation was named after Frederick Barbarossa – the 12th Century ruler over the Holy Roman Empire. Of the forces dedicated to fighting on the Eastern Front, three sections were established to cover the vast stretch of territory: Army Group North, Army Group Centre, and Army Group South. Their aims were to capture different cities within Soviet rule (primarily, Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev, respectively), and aid each other in overpowering the – as far as they were concerned – inferior force of the Red Army.

Prior to the outbreak of World War Two, Germany and the USSR had signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939, a pact of non-aggression meaning that the two countries could co-exist on the European stage without a threat of conflict between them. On a surface level, this was a successful agreement, with the USSR and Germany sharing Eastern European territories between them (such as Poland), despite their vastly opposing ideologies. It was this pact that initially led Stalin into a false sense of security, believing that Hitler would not break their agreement so soon after signing it. Therefore, when it became gradually more apparent that Germany was transferring its attentions over to the USSR, Stalin did not immediately prepare the Soviet army. Indeed, it was as early as August 1940 that British intelligence learned of the recently approved plans to invade the USSR, but Stalin did not believe the information when it was sent over to him. Furthermore, German intelligence leaked fake plans to invade the UK, and Stalin took the bait. It was not until May 5th 1941 that Stalin said ‘war with Germany is inevitable’.

In November 1940, Germany offered the USSR a position in the Axis Pact alongside Italy. The USSR declined, letting tension come into their relationship. A conflict between them seemed more likely from then on, and this was perhaps the turning point in Stalin’s attitude towards Hitler and his intentions. Shortly before staging the invasion, the Nazi party released propaganda within Germany which falsely suggested that the Soviets were planning an imminent attack. This was perhaps a bid to make the Nazi invasion seem more justified – a defensive move, rather than an offensive one.

Whilst the military prowess of Germany was well-known in Europe by mid-1941, the reputation of the USSR was less impressive. In truth, the Red Army was vastly inexperienced compared to the German Wehrmacht, but the USSR was much more industrialised that Germany believed; the Red Army was not as polished and professional as the Wehrmacht, but it was not wholly useless, either. The USSR in the 1930s had focussed large proportions of the economy into the development of the military, and though the Russo-Finnish War of 1939-1940 had been won with great difficulty, the capabilities of the Red Army were significantly underestimated by Hitler. Indeed, in the later years of the war, Hitler was reported to have said ‘if I had known about the Russian’s tank’s strength in 1941 I would not have attacked.’ (Barnett, 1989: 456)

Germany sought oil, labour, and resources, all of which could be gained by occupying territory within the USSR. A successful occupation would also isolate the United Kingdom, since a key ally would have been quashed by the Germans. The theory was that if the Red Army could be beaten, almost all of mainland Europe would be under Nazi control, and the surrender of the United Kingdom would be sure to follow. Hitler planned to starve a huge proportion of population to death, which would ultimately free up the resources to build up a new German aristocracy in Eastern Europe. He didn’t consider Moscow important in this campaign, placing more emphasis on defeating the Red Army rather than capturing the city; this was a source of much contention within the German High Command, since other Nazi officials disagreed intensely with him on this issue. St Petersburg (which was then known as Leningrad) was to be first target, and was the main area in which starvation was to be put into action.

The aim of Operation Barbarossa

The aim was a quick campaign, starting on May 15th 1941, and lasting between six and eight weeks. The fight on the Eastern Front was not expected to last into the winter, and therefore troops were equipped with a limited amount of clothing and supplies. There were roughly five million men in the Soviet armed forces in July 1941; 2.6 million of which were posted on the front against Germany compared to approximately 3.8 million German soldiers. Red Army could boast a large number of planes, but most of them were obsolete and old, and a lot of the pilot training was of a poor quality. The Red Army also had far more tanks than the Wehrmacht, but they were comparatively low in ammunition. The Wehrmacht overall was vastly more experienced than the Red Army, due to the intense military development undergone in Germany in the 1930s, and the military victories in France in 1940. Stalin had hindered the chances of the Red Army in his Great Purge of 1936-1938, which ‘removed’ most of the Soviet military High Command. This meant that, in 1941, the figures in charge of the Red Army were lacking in the experience that the Nazi military leaders had, and the army as a whole was not as polished and professional as the Wehrmacht.

The operation did not officially begin until 22nd June 1941; the ongoing Balkans campaign required troops and resources to be sent over to Greece and Albania, and so there was not enough man-power to begin Operation Barbarossa on May 15th. On June 22nd, Germany bombed areas in Soviet-occupied Poland without giving any warning or declaring war on the USSR. On that very morning, Hitler addressed his staff, stating that ‘before three months have passed, we shall witness a collapse of Russia, the like of which has never been seen in history’. The Soviet people were totally shocked and appalled by the sudden and unexpected assault, and the government rallied people by appealing to their sense of patriotism. This, however, did not mean that all Soviet citizens were united in the fight against Germany. Internal disagreements initially plagued the Soviet cause: the Uprising in Lithuania on June 22nd opposed Soviet rule, and led to Lithuania becoming independent. Further, the Battle of Estonia in July saw intense Estonian resistance to Soviet command.

The Wehrmacht had vast man-power not just from German citizens, but including military personnel from many Nazi-occupied countries. Fascist Spain, fresh from the victory of the 1936-1939 Spanish Civil War also offered support. The Luftwaffe was an impressive air force, and instantly gained air superiority. In the first week of the campaign the German Army Groups won significant victories in terms of territory, but at big costs in terms of man-power. In numbers, there was more damage done to the Red Army, (600,000 wounded, killed, missing, or captured), but proportionally, the Wehrmacht suffered the greater loss. The Soviet armies fought fiercely at every stage, which came as a surprise to the German soldiers, who believed the Soviets to be far less capable in warfare than themselves. This was one of the two biggest issues for Germany: the Soviet army had been grossly underestimated, (in numbers, ability, and industrial strength), and Hitler’s approach to the Operation differed greatly from that of the Wehrmacht officer corps. There were conflicting messages coming from different sections of the German High Command, which would lead to confusion, and misdirection.

The Second Phase of Operation Barbossa

The second phase of Operation Barbarossa – the Battle of Smolensk – took place over a month between July 3rd and August 5th 1941. Smolensk was a key region on the road to Moscow, and therefore it was vital for the Germans to successfully overpower the Soviets here in order to be victorious in the capital. The initial push towards Smolensk was hindered by weather conditions – harsh rainstorms – which slowed down the German army and gave time for the Soviets to prepare themselves. The Wehrmacht Army Group at work here was Army Group Centre, whose Panzer groups surrounded the Soviet armies, but could not achieve a complete surrender because of an increasing lack of supplies. After only two or three weeks, Hitler’s six-to-eight-week campaign was being threatened by dwindling resources. The underestimation of the Soviet army became evident here, and many soldiers from the Red Army were able to escape the German clutches at Smolensk and boost the numbers in Moscow, strengthening the position of the capital. The Wehrmacht officer corps passionately promoted the pursuit of Moscow, but Hitler – demonstrating the impatience that would thwart his plans of greatness – ordered that new tactics be followed, and demanded that Army Group Centre be sent to help Army Groups North and South instead of focussing on Moscow. This is considered by many historians to have been the mistake that turned the tide of Operation Barbarossa.

Phase three – Kiev and Leningrad (5th August – 2nd October 1941)

After a two-month-long campaign directed at Kiev and Leningrad, the Battle of Moscow finally began on October 2nd 1941. Hitler had redirected the Operation to the areas he considered more important, and, in doing so, begun a 29-month-long siege of Leningrad. This siege lasted from September 8th 1941 to January 27th 1944, which was the longest any German superiority was evident in Russian territory. The key tactic used during the siege was starvation, which resulted in the death of over 1 million citizens. In eight months between 1941 and 1942, 2.8 Soviet Prisoners of War were captured and killed in Leningrad. The siege left a huge imprint on the Soviet psyche, making the Red Army wholly unforgiving towards the Germans when the tide eventually turned.

Hitler turned his attentions back to Moscow towards the end of the year; this push towards the capital was given its own code-name: Operation Typhoon. In the time between October 2nd and December 5th 1941, the German Army Groups came within 90 miles of Moscow, but were once again hindered by incredibly harsh weather conditions. The muddy roads en route to Moscow, made worse by the intense rainfall, were difficult for the Germans to navigate, slowing down their progress. On October 31st, the Germans were ordered to pause so that High Command could review their strategies, which also gave the Soviets time to recover: they were able to organise 11 new armies within a month. The Germans were pushed to their absolute limit, recalling the issues faced by Napoleon’s army in 1812. The memory of the failed invasion by the French caused unrest amongst the soldiers, and even when the weather improved enough for advances to begin, the troops were drastically undersupplied.

Just as the Wehrmacht could see Moscow at the start of December, the weather began to deteriorate even more. The intense Russian winter began to set in, for which the Wehrmacht was simply not prepared. By this point, the campaign had lasted far longer than the six-to-eight weeks that Hitler had estimated, and morale was running extremely low. The Luftwaffe had been grounded by the blizzards, and a high proportion of the German weaponry was malfunctioning in the sub-zero temperatures. The Red Army was far more accustomed to the difficult weather, and therefore coped much better than the Wehrmacht: the Soviet aircraft was equipped with blankets to insulate and warm the engines in cold weather. At this point, the Wehrmacht suffered huge losses, and the Soviet counter-attack pushed the Germans back 200 miles. Food shortages and inadequate supplies tortured the Wehrmacht, and the troops never recovered. As a result of this dramatic turn of events, the German army began losing more and more territory in Russia, which eventually culminated in the Soviets advancing on the Germans, and invading Berlin in 1945.

Sources:

- David Stahel, 2009, Operation Barbarossa and Germany’s Defeat in the East. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Correlli Barnett, 1989, Hitler’s Generals. New York: Grove Press.

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_battles_by_casualties#Major_operations

- http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/operation_barbarossa.htm

Link/cite this page

If you use any of the content on this page in your own work, please use the code below to cite this page as the source of the content.

Link will appear as Operation Barbarossa – Key Facts & Information: https://worldwar2.org.uk - WorldWar2.org.uk, June 11, 2014