Six months after the destruction and belligerence of the attack on Pearl Harbour, the Imperial Japanese Navy and the U.S. Navy fought the Battle of Midway, lasting a matter of days between the 4th and 7th of June 1942. What ensued was the first Japanese naval defeat in 80 years: “The most stunning and decisive blow in the history of naval warfare” (Keegan, 2005: 275). The aim of the initial attack planned by the Japanese was another surprise wipe-out campaign, like Pearl Harbour, to destroy and demoralise the American Navy and gain control of the Pacific. A team of American code-breakers determined the plans long in advance and was able to prepare the fleet. A new Japanese codebook was not put into use until a few days before battle began, by which time the US was able to determine the key facts of the battle plan.

American Upper Hand

They suspected Midway was the destination, so leaked a false statement regarding the water conditions at Midway, which they then detected being transmitted between Japanese agencies, confirming all their suspicions. The defeat at was so absolute, Japanese military was unable thenceforth to replace ships or personnel at a fast enough pace, whereas the Americans were able to, allowing them to take the upper hand. The battle was an instance of rapid and dramatic change in power dynamic: “At ten o’clock that morning, the Axis powers were winning the Second World War… an hour later, the balance had shifted the other way.” (Symonds, 2011: p3-4).

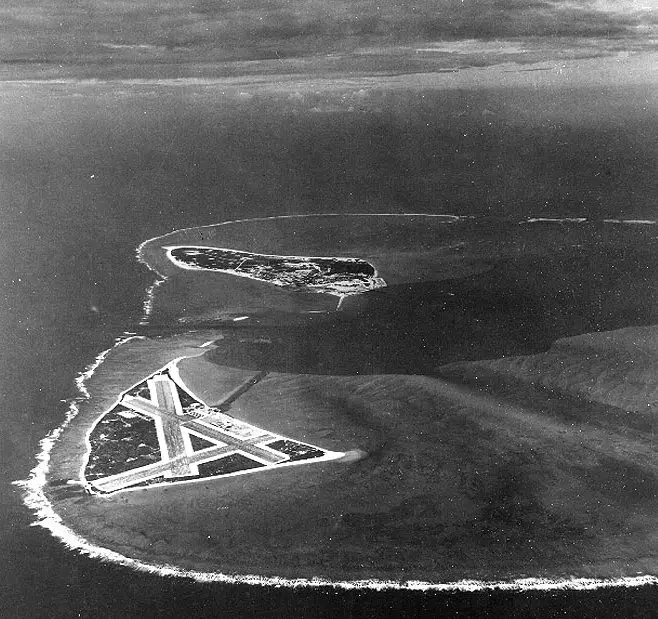

The Japanese psyche had been greatly affected by the Doolittle air raid in Tokyo on April 18th 1942. The Japanese military high command became more paranoid about the strength and aggression of America, and sought to eliminate them as a threat. The islands of Midway Atoll lie 3,200 miles west of San Francisco, and 2,500 east of Tokyo, almost exactly equidistant between the two combatants, (hence its name). The Japanese Admiral Yamamoto believed more US ships had been destroyed in the Battle of Coral Sea (4th – 8th May 1942) than had actually been, including the aircraft carrier, the USS Yorktown.

The Japanese psyche had been greatly affected by the Doolittle air raid in Tokyo on April 18th 1942. The Japanese military high command became more paranoid about the strength and aggression of America, and sought to eliminate them as a threat. The islands of Midway Atoll lie 3,200 miles west of San Francisco, and 2,500 east of Tokyo, almost exactly equidistant between the two combatants, (hence its name). The Japanese Admiral Yamamoto believed more US ships had been destroyed in the Battle of Coral Sea (4th – 8th May 1942) than had actually been, including the aircraft carrier, the USS Yorktown.

He also wrongly thought that US morale was wholly defeated by a string of minor Japanese victories. In his battle plans, he placed different formations very far apart in order to avoid detection, which meant they were unable to support each other: “had the IJN carriers been merged together, their attack, defensive, and reconnaissance capabilities would have been vastly improved.” (Grove, 2013: 22). The plan he created would potentially have been brilliant if it hadn’t been quite so intricate and complex, relying heavily on perfect, almost lucky timing. Japanese naval codes had secretly been cracked by US, giving America a “crucial edge” (Symonds, 2011: 5).

The Repair Job

The USS Yorktown was repaired within 72 hours of arriving at Pearl Harbour; it was in fact the Japanese Imperial Navy that had not sufficiently recovered from Battle of Coral Sea in time for Midway. Six months of constant operations had left the Japanese Imperial Navy exhausted, making them arguably predisposed to defeat at Midway. In the days leading immediately up to the battle, Japanese submarines were late arriving in position, so US fleets were able to assemble without being detected. The US Navy was very prepared, and the Imperial Japanese Navy believed they were. The US fleet was a much larger force than the IJN expected, and instead of adapting their battle plans, they were forced to follow the strict strategy that Yamamoto had implemented.

Initial hits on June 3rd by the US planes did little damage to the IJN. It was on the 4th of June that what we now call the battle began. At 0616 the Japanese bombed Midway, targeting the oil and power plants. US planes bombed the Japanese boats for hours with precision, destroying much aircraft in the process without sustaining too much damage to their own. Later in the morning, the US did suffer huge losses during a relatively unsuccessful attack, with only one pilot – Ensign George Gay – surviving the onslaught from the Japanese. During a slow and laboured re-fuelling process, Japanese carriers had a lot of planes on board awaiting attention, making them sitting targets for as yet undetected American dive-bombers. US tactics had smaller groups of aircraft attacking consistently throughout the day, whereas Yamamoto’s strategy dictated that an attack should wait until a certain number of aircraft can be assembled. This tactic of the Americans ensured that the Japanese were constantly bombarded with bombs, rendering them less able to coordinate a counter-attack. The early parts of the battle went almost wholly in the American’s favour; of the four fleet carriers the Imperial Japanese Navy started with, two were sunk by 1930 on June 4th.

Japanese morale was boosted by reports that two US carriers had been destroyed. In fact, both hits had been on same ship – the USS Yorktown – but an hour apart, in which time the carrier had been sufficiently repaired that it looked like a whole new ship. Neither attack sank the ship. This undue morale was destroyed when the remaining Japanese carriers were sunk a matter of hours after the first ones. In the early hours of 6th June, US ships intercepted what they later realised were Japanese cruisers sent to bombard Midway, and engaged in combat with them, destroying a large proportion of them.

The USS Yorktown was abandoned at 1500 on 5th June, but stayed afloat with the possibility of repair until it was sunk by torpedoes at 0600 June 7th. Despite the damage sustained to the Yorktown, the US ships and planes were able to secure a convincing victory over the Japanese: “What should have been a rout for the Japanese for the IJN ultimately saw the heart of its First Carrier Air Fleet, and all four of its carriers, sunk for the loss of only one US carrier” (Grove, 2013: 20). This victory was largely due to the fact that the

Americans were so prepared for the battle, but also because of the expert management of the US fleet, and the actions of the individuals involved: “The courage and skill of America’s dive-bomber pilots overbore every other disappointment and failure” (Hastings, 2011: 252). The Japanese forces were over-managed to the point of disorganisation, leading to confusion and a lack of adaptability when the US fleet was larger than expected. The Japanese lost 3,057 personnel over the course of the battle, and their carrier fleet never fully recovered. The pace of reproduction was much greater in the US forces than the Japanese, allowing them to recuperate much faster ahead of future encounters – “One of the cardinal misjudgements of the Axis war effort was failure to sustain a flow of trained pilots to replace casualties” (Hastings, 2011: 253).

Americans were so prepared for the battle, but also because of the expert management of the US fleet, and the actions of the individuals involved: “The courage and skill of America’s dive-bomber pilots overbore every other disappointment and failure” (Hastings, 2011: 252). The Japanese forces were over-managed to the point of disorganisation, leading to confusion and a lack of adaptability when the US fleet was larger than expected. The Japanese lost 3,057 personnel over the course of the battle, and their carrier fleet never fully recovered. The pace of reproduction was much greater in the US forces than the Japanese, allowing them to recuperate much faster ahead of future encounters – “One of the cardinal misjudgements of the Axis war effort was failure to sustain a flow of trained pilots to replace casualties” (Hastings, 2011: 253).

The Japanese tried to play down how large an impact the breaking of their code had; even the Japanese government were kept ignorant of the true extent of loss at Midway. In a play-by-play battle report submitted to High Command, Japanese Mobile Force Commander Nagumo wrote “the enemy is not aware of our plans (we were not discovered till early in the morning of the 5th at the earliest)” (Hone, 2013: 44). The fact that the code was broken would haunt the Jap efforts during rest of war. The news sent out to the general public was of victory; the wounded of the battle were hidden in secret hospital wards to keep the defeat undisclosed. The need to replace pilots very quickly resulted in their quality being drastically reduced; training was brief and minimal.

This defeat marked the beginning of the decline of Japanese naval air forces. Combined with the Battle of Coral Sea, the Battle of Midway removed any possibility of a Pacific victory for Japan: “The battles are the turning point in the course of the Pacific war” (Grove, 2013: 13). They instigated a shift in the power dynamic between the combatants: the Japanese fought a defensive war after Midway: “Though the war had three more years to run, the Imperial Japanese Navy would never again initiate a strategic offensive” (Symonds, 2011: 4). It took until roughly end of 1942 before sea superiority was established by the US Navy, but the Battle of Midway was instrumental in laying the foundations.

Sources:

- Philip Grove, 2013, Turning the Tide: The Battles of Coral Sea and Midway. Exeter: University of Plymouth Press.

- Max Hastings, 2011, All Hell Let Loose: The World at War 1939 – 1945. London: Harper Collins.

- John Keegan, 2005, The Second World War. London: Penguin.

- Craig Symonds, 2011, The Battle of Midway. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/battle_of_midway.htm

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/worldwars/wwtwo/battle_midway_01.shtml

- Thomas Hone, 2013, The Battle of Midway: The Naval Institute Guide to the U.S. Navy’s Greatest Victory. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Link/cite this page

If you use any of the content on this page in your own work, please use the code below to cite this page as the source of the content.

Link will appear as Battle Of Midway: https://worldwar2.org.uk - WorldWar2.org.uk, June 24, 2014